The camera market is a bastion of high tech as manufacturers constantly innovate to create market-leading products. Not only that, they appear to invest increasing amounts of money into research and development in order to stay relevant as the smartphone onslaught continues unabated. Or do they?

A plethora of products in recent years actually suggests declining investment as a way of minimizing exposure to risk. So what are manufacturers up to?

The playlist of technological development by camera manufacturers is remarkable as the boundaries of image-making were pushed back. The rangefinder Leica, SLR, auto-exposure, micro-electronics, auto-focus, miniaturization, digital, DSLR, IBIS, and mirrorless, to name just some of the game-changing shifts. These may evoke cameras such as the Nikon F, Leica M3, Minolta Maxxum 7000, Nikon D1, Minolta DiMAGE A1, and Panasonic Lumix G1 (or perhaps the Epson R-D1).

![]()

However, what this highlights is that the camera market has been driven by technological innovation. That’s not to say there aren’t gorgeously designed cameras — there are and anyone who’s owned a Leica M3 or Olympus Trip can testify to that — however, the market’s signature is innovation.

When you combine innovation with mass production and mass market, you create a rapidly evolving, dynamic, and exciting sector that is exactly what we saw around 2010 with the development of the mirrorless camera. The emergence of a new camera design is unusual in itself, but the design and production of new systems by every major manufacturer is unprecedented.

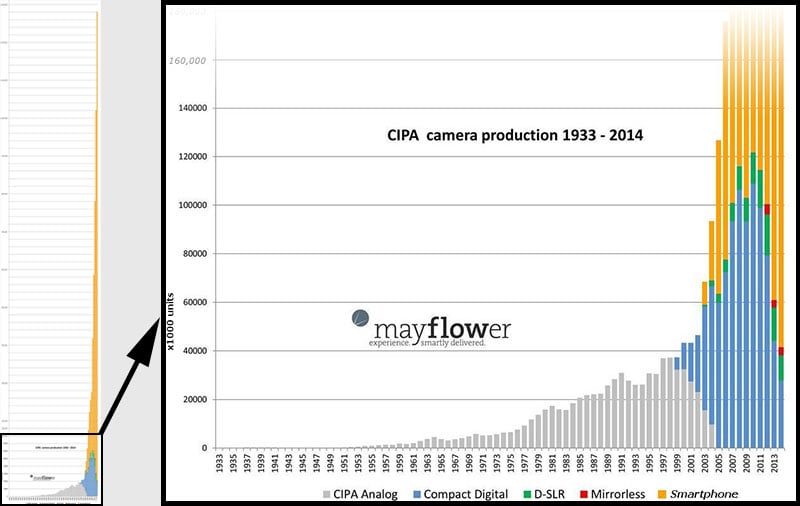

It wasn’t just that the mirrorless interchangeable lens camera (MILC) was here to stay, but that manufacturers saw it fitting into the existing market in different ways. It was always going to be disruptive and with disruption came change to the fortunes of manufacturers. Those fortunes were doubly impacted by the arrival of the smartphone; the camera market imploded, leaving manufacturers with declining sales at a critical juncture as the remaining consumers began to pivot to the MILC.

Manufacturing Trends

Against this backdrop, manufacturers have had to continue developing their systems, but the rate and scope of these developments are perhaps not entirely what they might at first seem. This can be highlighted with four trends that seem apparent.

Trend #1: Retro is the New Cool

Firstly, retro is the new cool, at least in the eyes of manufacturers. Fuji and Olympus have trumpeted the retro bandwagon for some time, however taking this a step further, why have one model when you can take existing technology and put it inside a different body? Nikon’s relatively recent Z fc builds upon its Df heritage to produce another retro-inspired camera.

Nikon actually has a habit of gradually evolving camera technology until the release of a new pro-spec body, at which point it makes a significant leap and then trickles this innovation down. However, the retro camera — in a range that is otherwise entirely “modern” — is an anachronism and speaks to a marketing department identifying a “segment” and then rapidly iterating a design to take advantage of it.

Is the Z fc a new model? Well yes in the sense that it has a new body with a smattering of new features, but is ultimately a Nikon Z50 in a different shell.

Trend #2: Product Personalization

Retro designs sell because of the vanity of photographers: you don’t just want a camera that is good, but one that looks good. The second trend we are seeing is personalization, a furrow that Pentax has been trying to plow. Take an existing design, allow the user to modify certain elements then get them to pay for the production, all of which potentially enables the manufacturer to extract a larger margin from an existing product with no extra work!

Pentax has said they want to move to a more “workshop-like” process which — pessimistically — appears to be no more than filling the gaps in a slowing camera release cycle.

A variation on this trend is the limited edition (such as Pentax’s special edition color KFs), something that Leica has consistently pursued. This creates scarcity (and so value) in production with very limited up-front costs to the manufacturer; for example, the Leica Q2 Ghost is about to go on sale and, while priced the same as a standard Q2, is intended to drive collectors to repeat purchases. This has worked for Leica because it can genuinely add value to a resale price, but whether Pentax has the cachet to achieve the same result remains to be seen.

Trend #3: Giving Cameras Facelifts

The third trend is the release of new cameras that are little more than a facelift. Pentax is guilty of this misdemeanor with the release of the KF which is a largely unchanged K-70 from 2016. The new model number was a surprise because the camera is almost identical, with part shortages driving alternative replacements.

Of course, this begs the question, when is a new model actually a new camera? What the manufacturer considers to be a significant deviation of parts may actually be almost identical in specification and functionality to the end-user. The OM System OM-5 also had minimal change — what pundits like to call a “refresh” — that saw a new processor as the most note-worthy.

Trend #4: Firmware Upgrades

The final trend is perhaps the most worthy: firmware upgrades. Cameras have always been defined by their hardware, but performance and functionality are increasingly being dictated by onboard processing, a trend demanded by smartphone users. It’s fair to say that OM leads the way in in-camera computational photography and the aforementioned OM-5 is a fine example of additional software functionality that genuinely adds value.

The other area of rapid software development has been auto-focus, with Sony, Canon, and Nikon all competing to have the best systems available. Nikon has been playing catch-up in this area and made a range of significant upgrades available to users, such as animal detection and better Eye AF.

The flip side of the software coin is that manufacturers have, in the past, been reticent to make substantial functionality improvements to old hardware, Fuji being a notable exception. We can’t expect manufacturers to make updates available indefinitely, however — as Adobe has shown — users are willing to pay a substantial subscription fee or one-off charges for additional functionality. I, for one, would welcome a more flexible approach to extending the life of existing hardware.

The Future of Sales

All that the preceding discussion highlights is that we are used to a technology-focused cycle of iteration for new cameras. The significant contraction of the camera market over the last decade has sent manufacturers scuttling off to find new ways to introduce greater breadth, and so greater sales, without such rapid development.

Perhaps one company that has managed to make this work for both it and the consumer is Sony. With the a7, it takes one body, shares components, and produces three variants that are technically similar but focused on changes to the functionality for the photographer. Not only that, but when a new model comes out, it keeps producing the previous version as a lower-cost model. This means there is only one cost sunk in the design and manufacture of a model and it is kept in production as long as it remains viable (in terms of sales and parts).

Whatever the future holds, the current period of mirrorless innovation will settle down as manufacturers try to compete with the smartphone.

Image credits: Stock photos and illustrations from 123RF