Photographer Jo-Anne McArthur has spent the last two decades photographing animals enduring pain while being used for food, entertainment, fashion, experimentation, work, or religious ceremonies. She has made it her life’s work to provide a voice and visuals that will show the suffering animals are put to, with the hope of reducing it, if not ending it altogether.

Warning: This article contains graphic photos that may be disturbing to viewers. Viewer discretion is advised.

“I saw virtually no coverage of these stories in the photo world and the media,” the Toronto-based photographer tells PetaPixel. “Activists did investigative work of this sort, and it wasn’t well done. Getting people to look at and engage in animal stories and suffering needed strong visuals and stories. I saw then that the work would be endless, as animal industries were proliferating in all countries.”

We Animals Media

McArthur came up with the We Animals project around 1998 after seeing a monkey chained to a windowsill in Ecuador.

“I created We Animals as a project long ago,” says the photojournalist. “2005? All of my animal work was housed in that project. Then I wanted to be more strategic with the work. What good was the project if I was out shooting 6-8 months each year, but the photos ended up on my hard drive while I went off to the next shoot?

“I was making the work so that it could help animals and help the campaigners helping animals. So, with help, I created the We Animals Archive, which housed my work publicly and was made available for free.”

![]()

When McArthur was starting, no one wanted these animal stories.

“When Redux Pictures first took my images for their stock site, they said they liked the work very much but didn’t think it would easily find a home,” she remembers. “Today, we know a lot more about animal sentience and how our treatment of animals is tied to many things: pollution, climate change, workers’ rights, and so on.

“It has become much harder to deny that animal stories are tied to important issues and that the animals live under terrible conditions that we would consider inhumane, or illegal, for our cats and dogs.”

The Patreon site of We Animals is currently generating $1,087 per month with a goal of $10,000 per month.

“We Animals grew from there,” explains the animal activist. “I started a Patreon, which very quickly led to a monthly income I could use to hire my first staff members. And I no longer had to shoot weddings, food, and events! Then we started fundraising in earnest, doing more projects, getting the work out farther.

“In 2019, we realized we were operating quite like a photo agency with several more staff, strategic plans, many more contributing photographers, and more operational capacity. We had a ‘Wait…are we a photo agency now?’ moment. So, we branded as such and launched We Animals Media officially that year. Now, we have over 20,000 [free] images and videos on our stock site from over 90 contributing photojournalists and videographers.”

McArthur (born 1976) draws a salary from her non-profit.

“I like freelancing but am proud that We Animals Media can offer me and several others employment and contract work,” she says.

![]()

Few people these days will use products made from endangered animals like Tigers (balms, etc.), but eating meat is normal for most people.

“Many more will understand eventually [about eating meat],” says McArthur. “Animal advocacy is thankfully multi-pronged. We have all sorts of efforts to help enlighten people about animals and animal sentience and that anyone who can suffer should be allowed to live free from inflicted suffering.

“This is happening slowly, but we see a little more enlightenment through the work of humane educators, lawyers, scientists, artists, philanthropists, and so on.

“A tiger is an elephant, is a cow, is a pig, is a fish, is a chicken, is a dog, is a human. We value our lives.”

Recording Animal Abuses

McArthur almost always works with NGOs while shooting. She was invited to Turkey to work with Eyes on Animals, a Dutch organization that helps companies and workers improve their animal farming, transport, and slaughter practices. Working with NGOs has taken her to about 60 countries.

“Sometimes we are stopped and questioned,” she says. “Sometimes we are welcomed. But we also work at night, entering farms to document things as they are and leaving without a trace. I’d rather not work this way, but most industries are not opening their doors to journalists, and these stories simply need to be told.”

The animal photographer tries to capture eye contact with her subjects when she shoots.

“As with photographing human animals, eye contact with the subject is a key way of creating a connection,” she explains. “ ‘Connection’ can lead to the important experiences of awe, curiosity, compassion, and action.”

McArthur has photographed cows being prepped for slaughter by firing a bolt from a stun gun to the head.

“It is meant to provide a more humane death,” she explains. “However, stun guns aren’t always used with 100% precision. So, you often see animals injured but conscious. ‘Humane’ is an industry word, but I don’t think there’s a way of killing humanely. To be humane is to spare one’s life. If a stun gun is used effectively, it lessens the trauma animals go through when being led to their deaths.

“Yes, we are seeing a rise in meat consumption in the BRIC [developing nations of Brazil, Russia, India, and China] countries and growing economies in general. This means a continued rise in industrial farming and the number of animals being raised and killed yearly.

McArthur would like to see a world in the future where animals are not raised for food.

“No one wants to live in a cage,” she feels. “No one wants a life of captivity and an untimely death.

“Eating more meat is associated with a rise out of poverty and a rise in social status, and people want that. It’s bad news for animals, but there are a lot of efforts to curb that.

“It may curb itself, as we also see a rise in zoonotic diseases [Ebola, salmonellosis, and COVID-19], which spread and kill us. We also see more people abstaining from eating animals on environmental, health, and ethical grounds. So, while there is a rise in veg*nism, there is also a rise in meat-eating. We have a lot of work ahead of us in curbing that.

“Animal products in fashion, animals used in entertainment, and cosmetic testing are declining. People are learning to adapt instead of buying animals [animal products.] There are [also] millions of domesticated animals that need homes.

“More countries are banning the use of wild animals in circuses, the import of trophy hunts, and animal trade (alive and their parts). I do see that the current massive frontier is the one that protects animals raised for food and aims toward the abolition of their use.”

The animal-loving photographer will have been a vegan for twenty years this coming April.

“I remember thinking that veg*nism was extreme and would be a life of deprivation, but when I made that first tentative foray into it, I saw pretty quickly that I would not go back to using animals,” she remembers. “I was surprised to experience how good I felt — intellectually, psychologically, emotionally, and ethically.

“I felt aligned with how I wanted to live in the world; an attempt to live with more expression of kindness and integrity. So far, so good. I have not died of a protein deficiency [she jokes].”

Photojournalists often put themselves in harm’s way to tell a story. We see more and more of them being persecuted, muzzled, and sometimes killed.

“We have more Ag Gag-laws [anti-whistleblower laws that apply within the agriculture industry] in countries, which make reporting on animal industries, or whistleblowing, illegal,” says McArthur. “And we have environmental journalists being killed a lot more now in countries like Brazil.

“There is a growing list of countries I would not want to work in. The work is getting more dangerous, but that won’t silence journalists and media makers from getting the stories that need to be told.”

McArthur’s photographs are sometimes published anonymously for her safety.

“At least a half dozen of the contributors to HIDDEN (the most recent book, 2020) use a pseudonym and never, in any way, reveal who they are,” states McArthur. “You get in trouble for doing this work! My work is published anonymously or under a pseudonym when I need to protect my ability to return to a country and live without repercussion in my own.”

HIDDEN: Animals in the Anthropocene

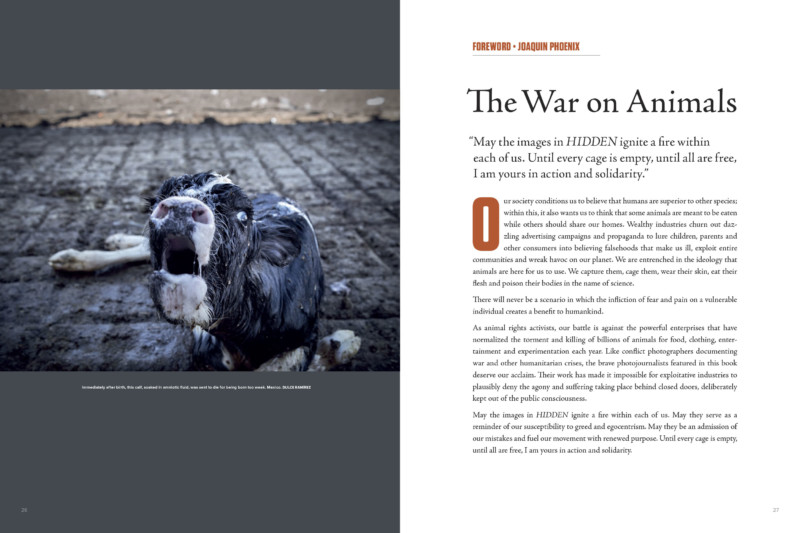

HIDDEN is the latest book published in 2020 by We Animals Media showcasing the images of animal abuse by 40 animal photojournalists, including McArthur. Her first book, We Animals, which took 13 years to compile, was published in 2013; her second, Captive, was published in 2017.

![]()

The publication zeros in on the close relationships between invisible animals and humans in their day-to-day lives. These are the stories of animals that are eaten, worn, used in research, or sacrificed in the name of religion. The stories are eye-opening and brutal, with the hope that future relationships with animals will be more humane and compassionate.

“I am, quite simply, in awe of these photographers. In a way, they are like war photographers, except they witness a war that so many people have little idea exists or choose to suppress that exists. This takes enormous inner strength and bloody-minded determination to illuminate the mass extermination that unfolds every second of every day across the planet.” – Nick Brandt, Photographer

![]()

McArthur met vegan, animal rights advocate, and actor Joaquin Phoenix on a few occasions at activist events in Los Angeles and London. She asked him if he would write the introduction to HIDDEN, and he agreed.

We Animals Media coined the word “animal photojournalist.” Animal Photojournalism (APJ) is an emergent genre of photography that captures, memorializes, and exposes the experiences of animals who live amongst us but who we fail to see.

Helping Animals Leads to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

McArthur was doing a lot of investigative work and early on was still fairly new to it in 2010, which led to a diagnosis of PTSD.

“I found myself waking in the morning, and the first thoughts and sights that would enter my mind were pigs in gestation crates, hens crammed into cages,” she recollects the scary scenes. “I couldn’t escape what I’d seen, which affected me profoundly. Therapy helped tremendously and does still, as I keep returning to the terrible things in the world and putting myself in harm’s way.

“But it’s also something I can and do live with. I think feeling traumatized is a natural response to what I’ve seen, and I know many caring people are traumatized too. If my work wasn’t effecting change, I couldn’t continue, but it is, so I have a lot of motivation. Not just me, but the growing number of animal photojournalists out there.”

The Cameras of the Trade

“My most beloved camera is my Nikon D4s,” says McArthur. I also shoot with a Nikon D850 and, now, a Nikon Z9. Yes, I am starting to move to mirrorless! Favorite lenses are my NIKKOR 17-35mm f/2.8, my 50mm f/1.8, and my 24-70mm, which accompanies my Z9. I have a few long lenses, but they spend more time in my camera bag.”

The Canadian photographer usually packs her bag with two bodies, four lenses, one hand-held LED light, batteries, and Hoya macro lenses [screw-on].

McArthur always hand-holds the LED light as she does not want it coming from the same angle as the lens. Her LED hand is very active, or she has someone on the team holding and moving the light around. She often shoots in low light and through bars and cages and must be very careful where shadows land.

“I’ve always been very chill about ISO, as I don’t mind grainy images,” she confesses. “I’ll often skip right to 3,200 ISO when I’m shooting at night, and now the mirrorless capabilities for extremely high ISOs are pretty phenomenal. I’m new to my Z9 [Nikon], so I’m just learning the beauties of high ISO.”

Adobe Lightroom is her favorite photo software.

McArthur has been influenced by the old school Magnum photographers, VII Agency, James Nachtwey, Sebastião Salgado, Larry Towell, and Aitor Garmendia. And photo editors like Margaret Williamson and Kathy Moran.

“I’ve been obsessed with photographs since I was a wee thing, but the photo-making started in earnest in 1997 when I enrolled in my first black and white printing class,” recollects the animal photojournalist.

“[I started with] wildlife, photojournalism, and conflict photography books, then a black and white printing class, and then it snowballed from there. A short internship with Larry Towell [war photographer and the first Canadian member of Magnum in 1988] then led to an internship at Magnum. That was in 2001. It’s been quite a ride!

McArthur studied English Literature and geography — double major at the University of Ottawa. She didn’t love it and was eager to be out doing things in the world. She wants to go back to school to learn new things and develop new skills, but instead of being a student, she finds herself invited to teach and speak at universities. The Denver University’s animal law program asked her for a week as a Distinguished Practitioner in Residence, where she gave talks, a workshop, a public lecture, and held office hours.

“My work overlaps with many areas, from the arts to sociology, science, and law,” she emphasizes. “I think I keep getting invited to speak at animal law conferences and programs because I’m on the front line with their clients – the animals.

“I’m bringing back evidence and their stories. As we know, stories are how information has been passed for millennia. The stories and visuals I collect are proof, and they get people closer to what’s going on in the world with others.

Awards Galore

McArthur’s work has received around two dozen awards, including Wildlife Photographer of the Year (x4), Nature Photographer of the Year, the Global Peace Award, Big Picture (Grand Prize!), AEFONA, and others. She loves jurying and has done so for World Press Photo and others.

McArthur flew to Australia to work with Animals Australia and Vets for Compassion to document the effects of fierce bushfires on animals. She was with VfC as they were getting starving, dehydrated, and injured koalas down from trees. There were a few bodies of bloated kangaroos lying around.

“But then I saw a few live kangaroos,” says the photographer. “I knew the photo I wanted, but I had a few hundred feet to walk to get it. That was a long walk! But I got it. And she hopped away.”

This image of the mother Eastern Grey kangaroo and her pouched joey (cub) surrounded by burned woodland won her the Nature Photographer of the Year award.

In another image that won her the Global Peace Photo Award presented by the Austrian parliament, an ape called Pikin, who had been rescued from poachers, sits on the lap of his keeper, who works for the animal protection initiative Ape Action Africa. Pikin is being transported after treatment at an animal clinic to a sanctuary in Cameroon.

McArthur feels that the image of the kangaroo and the ape could be classified as conservation photography or wildlife photography, but she still sees them as animal photojournalism. They are images of animals caught in the Anthropocene, affected by capitalism, greed, and ignorance.

“The work is satisfying when I know it will move people or make a strong statement,” she says. “But the work is never pleasant to pursue when I’m having to take risks to do the work and witnessing suffering.”

“Photos are moments in time,” says the animal photojournalist. “Static. But I want to create movement with images. Movement in our hearts and intellect. The photos I take should move people — to action, to caring, to change.”

In the distant future, McArthur aims to be less involved in the day-to-day activities of her organization, We Animals Media.

“Already, it’s in very capable hands,” she confidently exclaims. “As we continue to extract me from the garden. I call it ‘the garden,’ where we grow things, not ‘the weeds.’ I’ll re-focus on shoots, speaking, teaching, and writing.”

If you are interested in animal photojournalism, We Animals Media offers a 2 ½ hrs. masterclass for Canadian $45 (US $33). You can also contribute a photo or pitch a story.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: Header photo: (Left) Jo-Anne McArthur photo by Josee van Wissen, (Right) Jo and pig photo by KGuerin, Taiwan, 2019. All other photos supplied by We Animals Media and Jo-Anne McArthur.