Microsoft researchers announced a new AI called VALL-E that can mimic anyone’s voice with a three-second sample. Sure, it sounds cool, but are you not a little bit creeped out?

Malicious con artists can use deepfakes to misuse your visage for nefarious purposes, and now with VALL-E kicking off a new era of audio AI, tricksters can clone your voice and use it for whatever heinous plans they have up their sleeves.

How VALL-E works

To illustrate how VALL-E works, Microsoft placed audio samples into four categories and revealed the text VALL-E spits out after analyzing a user’s three-second prompt.

- Speaker Prompt – The three-second sample provided to VALL-E

- VALL-E – The AI’s output of how it “thinks” the target speaker would sound

- Ground Truth – The actual speaker reading the text VALL-E spits out

- Baseline – A non-VALL-E text-to-speech synthesis model

For example, in one sample, a three-second speaker prompt said, “milked cow contains … ” VALL-E then outputs its simulation of the target speaker. You can then check to see how close the AI’s output is to the real thing by listening to Ground Truth, which features the speaker’s non-AI generated, real voice. You can compare VALL-E’s voice-cloning abilities to a conventional text-to-speech synthesis model (i.e., Baseline).

Adding to the creep factor, VALL-E can also maintain the emotional cadence in one’s voice. For example, if you deliver a three-second prompt that is angry in nature, it will replicate your heated tone in its output, too.

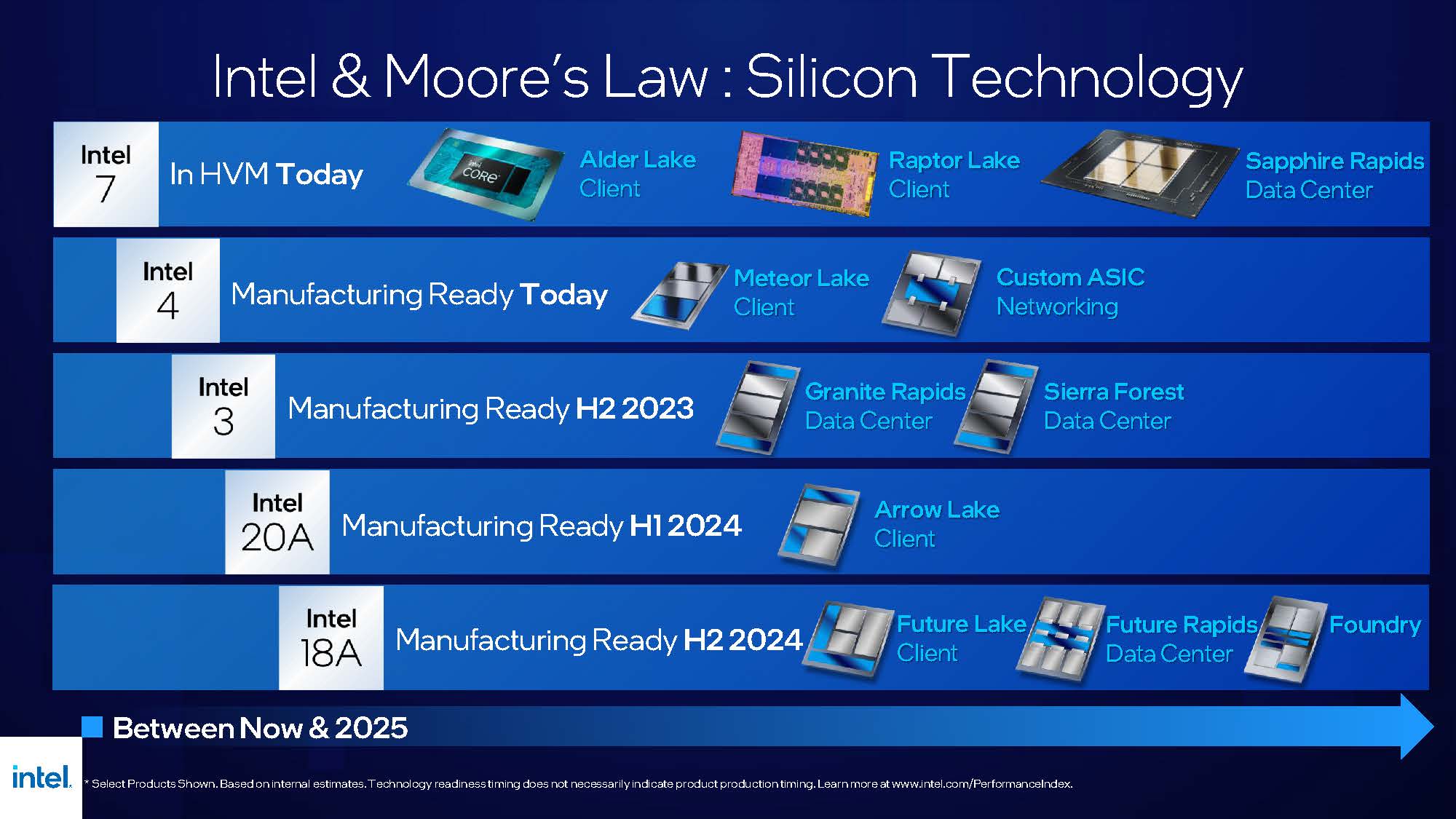

In the diagram below, Microsoft researchers illustrated how VALL-E works.

The researchers boasted that VALL-E outperforms the previous text-to-speech synthesis method, adding that it is better in terms of “speech naturalness and speaker similarity.”

I could see VALL-E being a huge benefit for giving a voice to robots, public announcement systems, digital assistants, and more, but I can’t help but think about how it could be abused if this AI falls into the wrong hands.

For example, one could snag a three-second recording of an enemy’s voice and use VALL-E to frame them as saying something abominable that could potentially ruin their reputation. On the flipside, VALL-E may become another scapegoat dishonest people could use to detach themselves from being held accountable for something they said (i.e., plausible deniability). Before it was “I was hacked!” Now, it’s only a matter of time before someone says, “That wasn’t me! Someone used VALL-E.”

As machine learning becomes more advanced and avant-garde, the line between humanity and artificial intelligence is blurring at an alarming rate. As such, I can’t help but wonder if our identifying characteristics, our faces and voices, are becoming too easy to clone.

Well, it seems like Microsoft researchers already foresaw the ethics concerns surrounding VALL-E and published the following statement in its report:

“The experiments in this work were carried out under the assumption that the user of the model is the target speaker and has been approved by the speaker. However, when the model is generalized to unseen speakers, relevant components should be accompanied by speech editing models, including the protocol to ensure that the speaker agrees to execute the modification and the system to detect the edited speech.”

To ease our fears, Microsoft added that one can build a “VALL-E detection system” to determine whether an audio sample is real or spoofed. Microsoft also said that it will abide by its six AI guiding principles: fairness, reliability and safety, privacy and security, inclusiveness, transparency and accountability.

Is this convincing? No. But at the very least, it’s nice to know that the Redmond-based tech giant is self-aware about the consequences of VALL-E.