“Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” said the business guru Peter Drucker, and Keith Clarke, a former Arm VP and 25 year Arm veteran, endorses Drucker’s view in his book ‘Culture Won’.

There was, of course, a bit more to it.

If Arm ever adopted a motto it would be: “I can do better than that” – the oft-repeated remark by Sophie Wilson, one of the two designers of the ARM 1 processor, who first used the phrase about a processor designed for National Semiconductor by her Arm 1 co-designer Steve Furber.

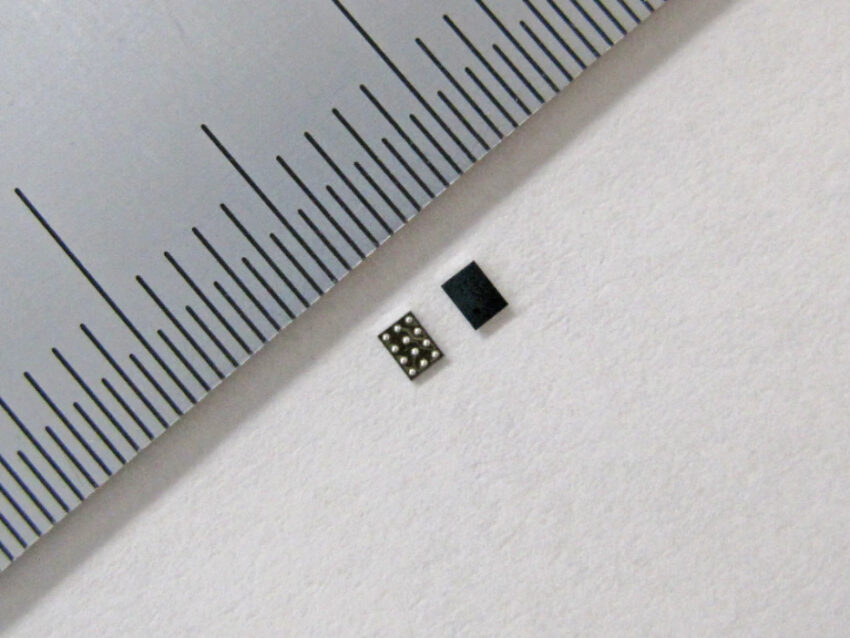

The remark sums up Arm which, throughout its progress from from twelve men in a barn to tech leviathan, has worked at the limit of what is technically possible – a discipline requiring a relentless drive to do better.

The toughness of Arm’s early days is shown in Clarke’s book by the reply of one of the twelve Arm founders – Lee Smith – when asked which cultural aspects most contributed to Arm’s success.

Smith referred back to Arm’s earliest days when the company was in its first office – a converted turkey barn at Swaffham Bulbeck just outside Cambridge.

‘Lee described the first two years as a difficult period where the “necessity to do what needed to be done… led to a strong culture of supporting one another”,’ writes Clarke, adding ‘Lee said they didn’t feel qualified to do what was needed and couldn’t afford the people that were. Lee’s summary was: “That was ‘We, not I’ years before we found that articulation”.’

From ‘We, not I’ evolved the concept of ‘Arm-Shaped’ people – a tag for people who were collaborative, constructive and able to see the the big picture of what Arm was trying to achieve.

There were reporting lines but no hierarchy – no feeling of distance between managers and team members, says Clarke. Performance reviews were based 50% on delivery against expectations and 50% on behaviour against the core values. This allowed managers to address the issue of high performers who didn’t work collaboratively.

At least one of the initial investors did not expect much. According to co-founder Jamie Urquhart, ‘Apple effectively wrote off its investment seeing the money as an inexpensive way to develop the CPU they needed’.

CEO, Sir Robin Saxby, encouraged the engineers to call the Arm licensees ‘Partners’ rather than ‘Customers’. Clarke says in all his 25 years at Arm he never heard a licensee referred to as a ‘Customer’.

Close connections were developed between the engineering teams and the Partners so that the engineering teams learnt to understand and sympathise with the goals of the Partners and grow a willingness to give up discretionary time and energy to meet Partners’ goals.

The value of those connections were that they ensured, writes Clarke, that “the voice of the customer was embedded in the Arm organisation.”

The real customers, however, were seen to be the OEMs to whom the Partners sold their silicon and who needed to be encouraged to create the pull from the Partners to order more chips from Arm to boost Arm’s royalties.

Saxby set up a system by which the company’s income came from both licence fees and royalties on shipped chips. In the early 1990s, 32-bit processors were becoming more in demand and the cost of developing them was high. The more people who licensed Arm’s designs the lower the license fee needed to be to cover the cost of the development. This benefited both Arm and its licensees, while Arm found that encouraging the businesses of its customer OEMs boosted the number of shipped chips and therefore royalties.

A smart piece of foresight by Saxby was to insulate the investors from operations. This staved off some tense moments at Arm when the investors were not happy about some of Arm’s operational decisions.

“Robin chose a holdings board management structure with the investors’ directors, insulating this from the operating company to prevent operational leaks,” writes Clarke, “this structure proved valuable in later years when ARM wanted to introduce the Thumb technology against Acorn’s wishes”.

The Thumb technology, implemented in ARM7, had been introduced to satisfy the demands of Nokia and Nintendo for greater code density. Acorn objected because the solution made them fear the loss of code compatibility with their own products.

The holdings board structure also proved useful when VLSI objected to the sale of a licence to TI on the grounds that TI was not only a commercial rival, but was locked in a legal dispute with VLSI at the time.

On both occasions the operating divisions had their way which was massively important in the case of the Nokia design win which was the key to Arm gaining 95% of the mobile processor market.

The holdings company structure, the licence fee plus royalty structure and the partnership culture reflected Saxby’s conviction from the outset that Arm would become a global standard.

Arm people have a USP – understated, looking for agreement, ready to listen but ready to offer solutions, smart but down-to-earth in an an industry where stubborn certainty is common but unproductive.

Arm was fortunate that its first two CEOs were outstanding people. Saxby personally embodies the values which made Arm successful and Warren East has an unerring eye for business opportunities which drove revenues from $213 million to $1.2 billion in his 12 year tenure.

Clarke’s book shows that Arm’s was not just a great technical success story or a great business success story but a great human success story. Talented people, believing in what they were doing, working collaboratively, changed the structure of the electronics industry.

Culture Won, by Keith Clarke, can be bought at Amazon, Wordery and World of Books.