Ghostwire: Tokyo shattered my spirit. The neon streets of Shibuya offer an alluring illusion, with Tango Gameworks’ sinister machinations coming to light only in the briefest of moments. This is a game that drove its claws through my chest and pierced my soul, rupturing its thin protective layer before striking at the core of my being.

Before I become lost weeping about the torment which afflicts me, I should provide some background. Interaction with the yōkai throughout Ghostwire: Tokyo most commonly revolves around acts of aggression. Well-groomed demons and vengeful ghosts love pelting Akito with projectiles while he’s casually strolling through Tokyo. However, there are yōkai that behave differently.

For example, the Karakasa-kozō, which is a bouncing umbrella with one eye, has to be snuck up on before being purged; getting spotted will only cause it to scurry off. The Kodama, which is a tiny forest spirit with a bush for a head, will hide in a tree until you destroy all of the yōkai seeking to harm it. To sum up, yōkai are either aggressive, skittish, or require the player’s aid. But there’s one yōkai type in Ghostwire: Tokyo that doesn’t fit under any of those categories.

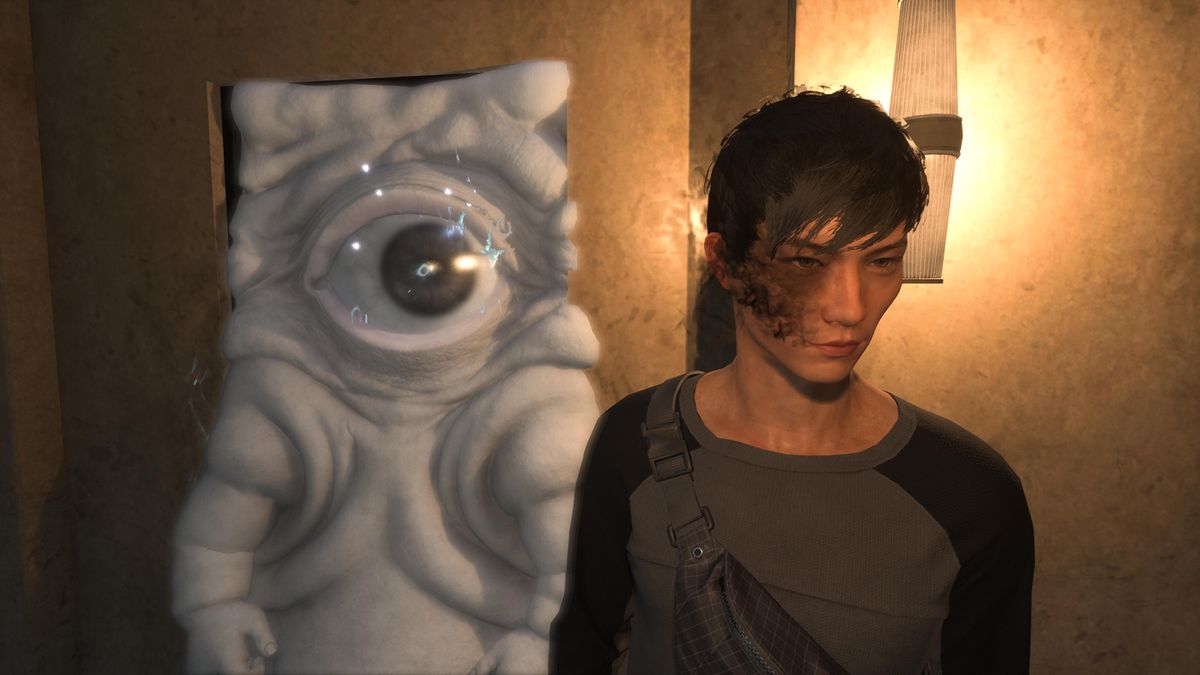

This creature remains motionless in its location, blocking hidden entrances that can only be revealed when using the game’s spirit vision. It doesn’t interact with the player; all it offers is a gigantic eyeball that tracks Akito wherever he stands. It’s not aggressive, it doesn’t run away, and there’s no method in which the player can offer it help. This is the Nurikabe.

Lamenting a loss

During a main mission in chapter three, Akito has trouble finding a path forward inside a cramped office building. KK suggests using spirit vision to uncover points of interest within the environment.

And that’s when it appeared; the derpy, pudgy, malformed marshmallow-creature that gently wrapped its stubby fingers around my fleeting soul and gave it purpose. At that moment, my heart was overwhelmed by a need to nourish it with the grandest meals a person of my income could afford. An uncontrollable instinct to provide this poor, innocent soul with warmth, comfort and a home burned within the once-cavernous organ that medical professionals call my heart. I was more than prepared to give up everything for this newfound friend; it needed a place to call its own and every fiber that makes up my being screamed to adopt it.

These joyous feelings have only come over me during the happiest periods of my life. But it was ephemeral, akin to the lifespan of all beings. Happiness turned into disbelief as I realized what Ghostwire: Tokyo expected of me. This Nurikabe, my child, the one I would call my kin, my own flesh and blood… I was expected to kill it. Its existence, however long or short it might have been, would end by my hand.

I had two options. I could remain forever with my newborn in this dreary office building and never finish Ghostwire: Tokyo. Or I could press on, adhering to the expectations of Tango Gameworks’ sinister game design, and do the unthinkable. Truthfully, I was more than ready to stick by the former.

But in a disgusting jolt of conscious obligation, the call of duty beckoned. I had to finish Ghostwire: Tokyo, no matter the cost. After all, I was in the middle of reviewing it. So… I purged my one and only, and at that moment, the faint light that resided deep within was smothered.

It took me a never-ending few minutes to get over this momentous loss. But looking back, I now wonder: What even is a Nurikabe?

Digging into the Nurikabe

During my encounters with the Nurikabe, Ghostwire: Tokyo didn’t make it clear what the yōkai signifies. It conceals hidden passages, and when close enough, it repeatedly says “wall.” But why is it there? What causes it to form? And is there anything that makes it particularly dangerous?

Ghostwire: Tokyo features a database with logs of its characters, including the Nurikabe. There are interesting tidbits in here, like how legends state that you must sweep the wall from below with a stick to make it disappear. The barriers these yōkai create can be “infinitely wide” and prevent any kind of circumvention. And the walls of a Nurikabe can be entirely invisible, which makes me wonder if it causes a psychological affliction that prevents people from traversing certain paths.

Nurikabe aren’t rare in video games, either. The Nioh series features a rendition of the Nurikabe that conceals hidden passages, with the only hint towards its existence being the slit of the two eye holes in a wall formation. If you hit it enough, the Nurikabe will reveal itself with two giant arms and begin thrashing you mercilessly. I can confirm that this version of the Nurikabe is nowhere near as lovable as the one in Ghostwire: Tokyo.

While it hasn’t been confirmed by anyone at Nintendo, the Whomp and Thwomp enemies from the Super Mario series are likely inspired by the Nurikabe. Whomps are walking walls with arms and legs that will crush Mario if he isn’t careful, while Thwomps move in a set vertical pattern before slamming on the ground.

The earliest illustration of the Nurikabe (that scholars are aware of) is found in the “Bakemono no e” scroll, believed to have been illustrated in the late 1600s or early 1700s. Currently, at the BYU Library in Utah, this massive scroll depicts 35 bakemono (monsters) throughout Japanese folklore. The Nurikabe is one of them, featuring three eyes, a massive nose, and floppy white skin.

Scholars think the earliest prominent written reference to the Nurikabe came from Japanese folklorist Kunio Yanagita, who was born in 1875. His first book, Tōno Monogatari, was published in 1910 and is praised as a classic collection of Japanese folklore. According to the BYU Library, Yanagita had recorded local folklore regarding the yōkai on the island of Kyushu in 1933, which is considered to be the originating point for the exact details regarding the Nurikabe.

It’s believed that the Nurikabe exists to obstruct a person on their journey, whether that be through the blatant presence of a wall, or some sort of invisible force that blocks pathways. This yōkai is why people get lost when traveling for long periods of time, as it can infinitely stretch in any direction. Some think that tanuki (Japanese raccoon dogs) use the Nurikabe as a mischievous method of messing with travelers. Similar to what Ghostwire: Tokyo alluded to, hitting the ground at its feet with a stick causes it to vanish.

Besides that, its history is a mystery. There’s no telling why they truly appear, or if there’s a more elaborate reason it exists. I was initially curious if the Nurikabe had a personality or possessed a deeper emotional reason for its appearance within Japanese folklore, but I have even more questions now than I did before.

Bottom line

Understanding the Nurikabe has helped me come to terms with why I had to do the unthinkable. Akito and KK needed to absorb this yōkai and continue their journey. Parallel to the folklore itself, I would have had my progress through the game’s main campaign halted if I had not dealt with it. Akito needed to find his sister, KK wanted to save the world, and I had to finish a game review. We found ourselves on a voyage and could not proceed due to the presence of this incorrupt being.

But I wish things were different. This cruel, unjust fate elicits a bittersweet regret. The death of this precious thing sits as heavy as an anvil upon my weary bones. I write this for you, my beloved Nurikabe. We will meet again someday, even if it’s in the afterlife.