Within humanity exists a searing hunger to chart the untold. To plunge into unfamiliarity’s fiery embrace. To liberate oneself of the known, the reported, the published. Within us is a desire to “experience.”

Adventure stirs inside the guts of an average person. Deep down, they seek to abandon the shackles of structure and preconception. To focus on that which they can see, hear, and feel. To ignore what they are told and, instead, wander.

Unfortunately, video games are regularly tethered to a composition that betrays the adventurer and smothers the wanderer. Open-world games, in particular, refuse to leave questions unanswered.

“Where do I go next?” has an answer. It’s offered through dialogue. It’s presented in a map marker. It’s guided by a gigantic arrow. The question is obscured by the GPS that pervades modern game design.

“What do I get out of this?” has an answer. It’s offered through an exorbitant amount of loot or experience to level-up. It unlocks the next mission and pushes the narrative forward. For some players, it’s the promise of a platinum trophy; the ephemeral adrenaline received from the ding of an achievement unlocked can be irresistible.

“How many secrets are there?” has an answer. Those “secrets” are drowning in a map overwhelmed by markers depicting collectibles. Climb a tower to reveal exactly what this game has to offer. Open the menu and notice the ever present percentage value reminding you of how much you’ve done and how much remains. Letting the player be surprised by any facet of the game is the antithesis of this design.

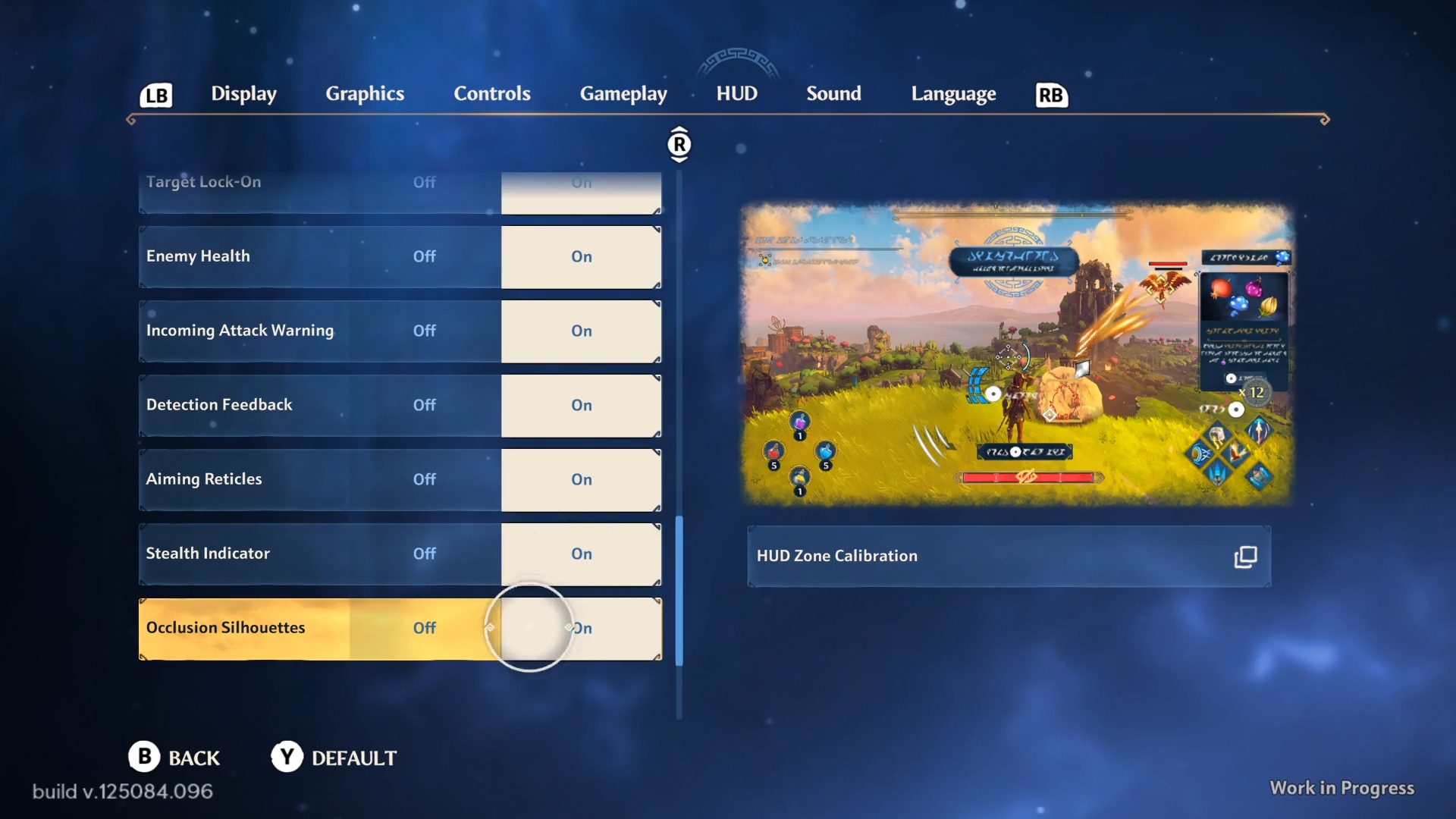

“What’s the objective?” has an answer. It’s shoved onto a corner of the screen at all times, and depending on the game, it’s present within multiple facets of the UX. Sometimes without even having to enter a menu, you’re treated to a quest log, an arrow to follow, and a mini-map with many little dots.

These elements are explicitly communicated. Rarely does the player get a chance to ask and answer the aforementioned questions for themselves. Because the modern game’s goal is to get you to the finish line, not to ensure you’re experiencing every step of the journey.

The Lands Between liberates us

By abandoning the explicit answering of its own questions, Elden Ring thrives off of the adventurer inside us. It supports the player’s curiosity. No quest logs. No mini-map. No collectible trackers. No overly apparent UI elements aggressively nudging the player in a specific direction. No linear method in which a player must engage with content. No constant reminders about how much game is left. To FromSoftware, what’s “worth doing” is entirely up to the player.

Every event and interaction exists for the sake of existing. A player can wander wherever they please, and although there is a certain method in which end credits are reached, most of the experiences within this world can only be found by asking and answering the aforementioned questions yourself. Players are encouraged to keep their own quest log in the form of notes, and create their own map markers to chart their journey.

Elden Ring is an authentic open-world experience, and although it’s not perfect, its structure evokes a potent freedom that other games in its genre desperately need. The vast majority of open-world games out there present ideas that so strongly push against the cores of Elden Ring’s phenomenal design, and after the game’s massive success, it’s about time the industry pays attention.

The importance of presentation

Presentation—especially UX and UI, which make up a game’s interface and involve the player’s experience interacting with menu elements—might seem detached from a game itself, but if an open-world is overly guided, too informative with its map markers, and features quests that hold the player’s hand at every step, the content will be approached as if it’s something to complete rather than to experience.

Generally alluded to as the feeling of being trapped by a set of “chores,” turning a game into a list of symbols to check off one by one is detrimental. When players scan their map more than the game’s environments, they’re probably invested in completing the game, but that’s not necessarily a good thing.

An open-world is cheap without exploration. If a player has nothing to discover due to an overly informative UI, they’re merely an overwhelmed tourist. Fast traveling from one point to another to pick up every arbitrary collectible is akin to hopping on a New York City train and riding between its most popular landmarks. You’ll still fall in love with the city’s beautiful sights, but there’s nothing better than wandering around the streets of Manhattan to truly absorb its distinct architecture and culture.

This feeling of wonderment is an important reason why Elden Ring and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild are the most acclaimed open-world games in a decade. Opening the map offers minor hints for what to expect from the landscape, but the stories, sights, creatures and characters that lie within each area must be charted first-hand.

This refusal to put exploration in the player’s hands even seeps into in-game dialogue, where the protagonist will speak to themselves about which direction to go or provide hints for solving a puzzle. This is designed to convince the player that the protagonist exists, reacting to the world around them. But these forced exchanges usually feel like a cheap way for developers to control the player’s journey.

The benefits of a limited narrative

The term “open-world” has a specific connotation attached to it: An expansive area that features optional content, but reaching the credits is achieved through a linear method. The separation of “side quest” and “main quest” is how nearly every game in the genre categorizes it.

But it’s almost as if there are two separate games here. One allows the player to go in any direction, fight monsters, discover vistas and run errands. The other is limited to a rigid path forward and commonly cannot be altered or tackled in a unique order. It’s more accurate to call these experiences a “linear open-world.” You can (usually) engage with the optional content in any sequence at any point, but the requirement to push the often-cinematic narrative forward is achieved by doing one main mission after the other. And even then, the former isn’t always true, as some open-world games limit new areas behind story progression.

This structure isn’t inherently detrimental, but it’s worth making the distinction between this style of game and what sits closer to a “true” open-world. Breath of the Wild and Elden Ring have moments of linearity, capping off with an unchanging final area and boss to reach credits. But the method in which players reach its finale is never rigid.

In Breath of the Wild, you can rush straight towards Calamity Ganon after the tutorial, skipping every shrine, cutscene, Divine Beast, and ignoring the introduction of its many characters. Hyrule Castle is always approachable; there are no artificial barriers that limit the player because “they aren’t ready.” If you think you’re ready, you can tackle the finale at any point.

Once the player steps into Elden Ring’s open-world, an enormous golden tree signifies the objective. This colossal, ever-present beacon growing out of the side of a mountain acts as a guide. That’s where the player must go; everything else is up to them. By providing an unchanging goal, the player will learn to start their own quest log, place their own markers, and seek personal feats.

If a player runs around an environment for an hour before being tethered back to a linear campaign, that’s not freedom. The developer is deciding how they can explore this world, limiting them to a strict set of conditions before certain areas are unlocked. Games need a “win” condition to reach credits, but if the player can avoid the linear section for as long as possible, they will feel liberated. It took me 80-90 hours to get to the Erdtree in Elden Ring, and up until that point, there were no barriers determining what I could do or where I could go.

Climbing the tower

Colloquially referred to as the “Ubisoft tower,” this open-world trope was popularized by the Assassin’s Creed series. It always features a map that is broken up into chunks, and interacting with a certain type of object (or character) placed throughout the open-world reveals new parts of it. Whether this is through the Sheikah Towers in Breath of the Wild or Tallnecks in Horizon Forbidden West, climbing something high to get a bird’s eye view of the area and unlock a new piece of the map is common for the modern open-world game.

Towers (or any tall object) aren’t even necessary for this trope, as Elden Ring features map pieces scattered throughout the world on the ground level. We can boil this mechanic down to the concept that a huge chunk of the player’s map is not visible when they start the game, and rather than it populating while walking through it, it expands after further interactions with a certain classification of object.

While this system is frequently criticized within the industry, it can work. In Elden Ring, it allows the player to gradually uncover the true mass of The Lands Between. Initially having access to just a portion of one region (Limgrave) and slowly seeing it grow provides an intense realization regarding the game’s scope. It’s beneficial to the exploration to give the player a chance to focus on what they can see in the moment as opposed to getting distracted by the sheer size of the world.

The towers in Breath of the Wild act as parkour puzzles and end in a gorgeous view of its colorful environments. Once successfully climbed, players can use their Sheikah Slate as a scope and place markers around unique creatures, shrines, villages or other points of interest. This is most effective thanks to separation between the tower’s in-game existence and developer guidance. Breath of the Wild allows the player to chart their own course, and Elden Ring offers a simplified map without much hints towards its deeper workings.

Other open-world games implement “the tower” as an omniscient satellite; points of interest—whether they be side-quests or collectibles—are placed throughout the in-game map and sometimes appear on the screen itself. Removing player agency in this way leads to an exhausting routine: Climb the tower (or whatever is required of its interaction), pick-up every collectible, complete each side-quest and repeat.

Other games, like Ghostwire: Tokyo, go even further by limiting exploration to the player’s progress in the main campaign. Not only is the map obscured if they haven’t cleansed a torii gate but they cannot physically travel in that direction. A deadly fog permeates Shibuya, and staying within for too long will cause the player to die. This ensures the game’s earlier chapters are always forcing the player along a linear path, one which seems antithetical to the goals of an open-world.

By treating “the tower” as a way to gate progress and reveal every secret the world has to offer, an open-world game veers into the linear. This routine is exhausting, but this mechanic does not have to be synonymous with that foundation. Having players discover new map chunks can be exciting, and with Breath of the Wild allowing the player to set their own personal goals, this system shines.

Rewards fuel actions

Why should a player engage with rewardless content? An open-world with quests that offer no currency or equipment and foes that drop nothing but the satisfaction of their defeat seems unfeasible; we’ve become comfortable with the idea that an action is only worthwhile when it yields something tangible. It’s difficult to imagine that players would see the omission of these elements as anything other than a massive flaw.

Without a bounty for completing a quest, players walk away with only the experience (not the XP variety). A side-quest boasting excellent writing wrapped up in a fantastic visual set piece that caps off with a memorable bossfight should stand independently. When characters are interwoven into the narrative in a compelling way and every step of this corner of the world evokes intrigue, the lack of rewards should not sour the experience. Breathtaking moments that stick with the player years after hitting credits must take priority over a new weapon or pouch of gold.

Optional content of this quality is exceptionally rare because side-quests revolve around the reward rather than the content. They’re excuses to pad the time it takes to level up, get more currency in the player’s pocket, and throw them new armor to equip. It’s an addicting affliction that tricks us into thinking that these elements need to be present for a sense of progression. Acquiring gold, skill points, armor, weapons and abilities distract us from the tedium of the average open-world.

A game can have superb optional content and worthwhile rewards simultaneously, but it’s generally treated as a half-baked necessity as opposed to a compelling way to bolster player agency. Especially when the developer must find an avenue for the ridiculous amount of loot the team has created, a quick and easy method of getting it in the player’s hands will be implemented.

Even Elden Ring suffers from this flaw, as players will navigate repetitive minor dungeons and ruins that exist to provide an item at the end. There are a few unique twists here and there, but these get rather tedious. Strip these sections of their loot, and their purpose is moot due to many reused bosses, enemies and assets. Yet if you were to strip the game’s massive castles of their loot, they’re still phenomenal, boasting unique sights, excellent bosses and exciting level design. It’s as if players are expected to enjoy uninspired content when it offers some sort of reward.

The unreliable side-quest

Side-quests have become a staple of the open-world. Letting the player choose what to do or where to go can be an incredible feeling, and optional content is the easiest way to achieve this. However, the trend to include them usually feels like nothing more than a necessity to fit in. “Side-quest” is a buzzword that allows the game to utilize its most uneventful content and repurpose old areas, enemies and bosses.

Final Fantasy VII: Remake’s side-quests keeps the player in a specific area, often forcing them to retread that zone, fetching items or fighting a specific group of enemies. These never take the player to fresh setpieces (at most, a new room will be unlocked) and rarely introduces them to a new enemy type. The game’s coolest side-quests are the ones that allow the player to fight iconic enemies like a Tonberry or a Behemoth. The game features 26 side-quests, all of which I completed, and only a few of them were memorable due to the inclusion of unique elements.

If a side-quest is not offering the player something new to engage with, whether it be through the form of a fresh narrative arc, enemy type, location or bossfight, it feels like filler. And even in the cases when a story is being told, it’s easy for players to tell when it’s written with little to no thought.

Nioh, although not an open-world game, features side-missions that are predominantly made up of repurposed main missions that players can traverse in a slightly different manner. These exist to refight bosses or stronger versions of already introduced enemies. There are a few side-missions that feature new areas, but these also get repurposed quickly. Players are forced to engage with this content to level-up, but the game would be better off if they weren’t there at all.

Adding content for the sake of it is always detrimental. Quality over quantity is one of the most common sayings in history, yet this philosophy is rarely applied. Unless a side-quest has something unique to offer, it probably shouldn’t exist.

The overused power level

Plenty of open-world games assign a “score” to every equippable item the player can get their hands on. This is a quantifier for the object’s power in accordance with the game’s algorithm. It essentially suggests “this thing is better than that other thing because its number is higher.”

“Which weapon is better?” is a question the game has an answer to, denying the player’s prerogative to equip based on their own preference. By assigning an objective quantifier of power, the “looter” system often betrays player agency. These games are mindless as a result, offering dozens upon dozens of meaningless item drops that all must be dismantled or sold without a second thought because the only thing worth using is the one with the bigger rating.

This usually stops being an issue towards endgame, as item levels stagnate at a certain value. Once players hit max level in The Division 2, they can consciously build out their character in unique ways because every drop has an almost identical item level. By that point, the stats themselves are the focus, but it’s an awfully mindless grind to get there.

Games like God of War (2018) even go so far as to make equipment item level necessary for progression. Kratos is assigned with an overall “power level” and it is the most important stat in the game, as it determines how easily enemies can be staggered and greatly enhances the damage he deals. Even though there’s strength, defense, runic, vitality, luck and cooldown, the goal is always to find gear with a higher power level, regardless of its actual stats.

Equipment is nearly pointless if the player has minimal input in deciding its worth. This system provides a simple way to throw dozens of shiny bits of loot at the player’s feet and engage with the part of their brain that loves to see stuff glow, but it rarely offers real depth.

Item-scores aren’t inherently like this, however. Certain games are intentionally stingy with their loot-drops to focus on rewarding the player for achieving feats. If you beat a challenging boss, you’ll get good loot out of it. Players don’t have to feel overwhelmed, and can still make a few decisions in what they equip. But something like Borderlands throws an absurd amount of guns at the player and they all feel worthless.

My inventory fills up in less than 30 minutes while playing Tiny Tina’s Wonderlands, to the point where I might as well just stop picking stuff up. The game has completely removed the excitement of seeing loot drop; it has no novelty anymore and my mind deteriorates when bombarded with useless flashy garbage.

There is no algorithm or objective values to express one weapon is better than the other in Elden Ring. You can freely decide which moveset best fits your playstyle, and when you find something suitable, it can be taken to the end of the game. Absurd quantities of loot are never thrown at the player’s feet; unique weapons and armor can only be found once, which makes them genuinely feel special.

Breath of the Wild takes a different route with this approach, assigning a durability value to every weapon the player can find. As a result, you’re always conscious of the weapon you’re using, and depending on the enemy, you’ll have to switch between them frequently. Although certainly unique, it forces us to be thoughtful about which weapons we use and pick-up at all times.

The success of evolution

Every few years, an open-world behemoth that sets trends and defies preconception falls in our laps. Just over the last five years, we had Breath of the Wild in 2017 and Elden Ring in 2022.

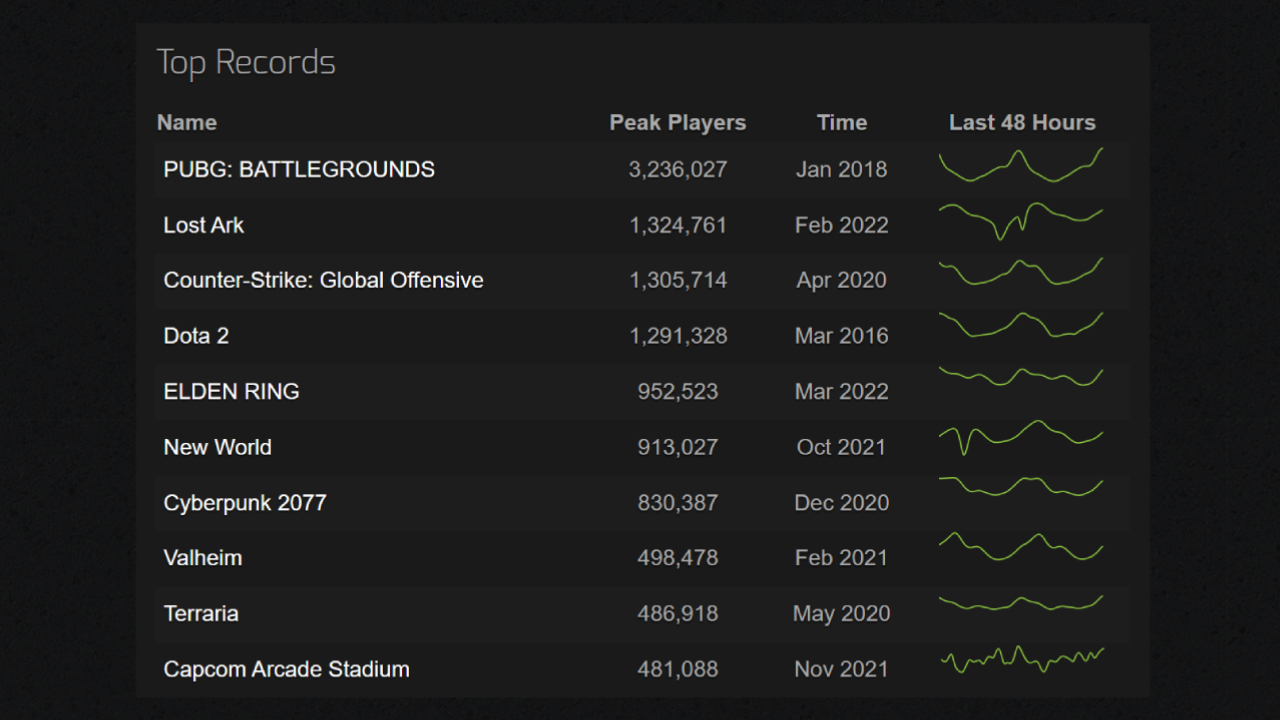

Both are the most financially successful in their respective franchises, also boasting some of the highest critical scores of all time. Revolutionary in their impact on the medium, these prove that an open-world done “right” can overpower almost anything else gaming has to offer. While it’s too early to predict overall sales, Elden Ring has broken records, boasting the highest peak player count of any full-priced game on Steam.

Players of all kinds, whether fans or critics, put great value in agency. These are all titles that allow us to ask and answer. Discovery is in our hands, and when analyzing the trends found in other open-world games, the potency of this sensation is seemingly underestimated by the industry.

Many of the open-world tropes criticized in this very article come from some of the most successful open-world games ever. The mission-based open-world was popularized by Grand Theft Auto III, and Rockstar is still finding monumental success with Grand Theft Auto V and Red Dead Redemption 2. Looter systems blew up after Borderlands 2 (although Diablo featured similar ideas many years prior), with the game sitting on the list of top 50 best selling games ever.

As a result, I’m not expecting the financial and critical success of Elden Ring to inspire the industry to take more risks and push the envelope for what’s possible in the genre. After all, this didn’t happen with Breath of the Wild. Elements of its formula can be found in games like Genshin Impact and Immortals Fenyx Rising, but all this has done is set a new trend that will similarly be overused throughout the next decade.

Bottom line

The traditional open-world is often derivative, repurposing historically profitable trends while ignoring the potential of its evolution. After all, it is one of the most successful genres in the medium. Tackling a tried and true formula in ways that step outside of expectation is a risk most companies will never take.

But some games question what openness can elicit. These challenge the open-world, expanding its foundation in service of invoking genuine freedom. And the response, both financially and critically, has been staggering. The power of a liberating open-world should never be trivialized.

Player-fueled adventure, in most cases, must be a core tenet of the open-world. If not, what makes this world open? If a game does not allow the player to completely break away from the path laid out by the developers, it’s difficult to see that as anything other than “linear.”

Openness revolves around the player. It’s about our ability to ask and answer questions like “Where do I go next? What do I get out of this? How many secrets are there? What’s the objective?” If a developer is asking and answering these questions for us, they’re in control, and the world isn’t truly “open.”