This year marks 50 years since Susan Sontag’s essay “Photography” was published in the New York Review of Books. Slightly edited and renamed In Plato’s Cave, it would become the first essay in her collection On Photography, which has never been out of print.

The breadth of “Photography” is immense. It ranges over artistic, commercial, photojournalistic, and popular uses of photography; and it discusses the photograph’s role in both sensitizing and desensitizing us to other people’s suffering – a theme Sontag reconsidered 30 years later in her final book, Regarding the Pain of Others.

But perhaps nowhere is Sontag’s enduring relevance as a critic clearer than in the essay’s analysis of photography as both a symptom and a source of our pathological relationship to reality.

Sontag described photography as “a defense against anxiety”. She saw that it had become a coping mechanism. Confronted with the chaotic surfeit of sensation, we retreat behind the protection of the camera, whose one-eyed, one-sensed perspective makes the world seem maniable.

Sontag claimed that we photograph most when we feel most insecure, particularly when we are in an unfamiliar place where we don’t know how to react or what is expected of us. Taking a photograph becomes a way of attenuating the otherness of a place, holding it at a distance.

Tourists use their cameras as shields between themselves and whatever they encounter. According to Sontag, photography gives the tourist’s experience a definite structure: “stop, take a photograph, and move on.”

Having taken a photograph, we think of its subject as our captive: it’s there now, on the film, in the camera’s memory. This can make us inept observers. There is no need to experience something now, as we can always review it later. So we grab and run.

Even if we compose carefully, if we “make” rather than “take” a photograph, we are likely to feel the release of the shutter as the release of a bond, as if we now can (or must) move on – to other photographs.

I Was There

Photography is a way of testifying I saw this, I was there.

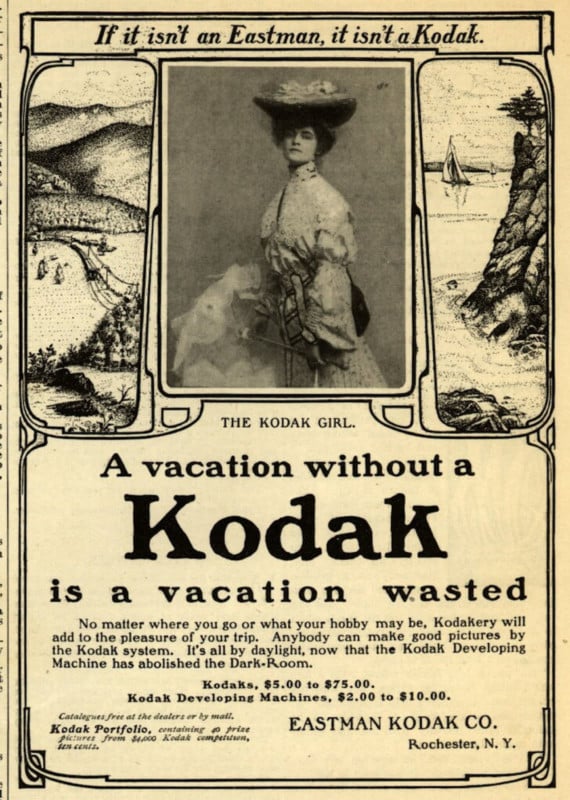

Kodak’s marketing through the early 20th century testifies to this urge. “Take a Kodak with you” was one of the company’s earliest slogans. By 1903, they were announcing that “a vacation without a Kodak is a vacation wasted”.

Sontag wrote:

A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it – by converting experience into an image, a souvenir. Travel becomes a strategy for accumulating photographs.

Through photography, Sontag argued, we sooner or later become tourists in our own reality. Sontag thought this happened mainly to the photojournalist, the person on constant lookout for their next subject. But it is true of most of us today. We have become discontents on the perpetual lookout for content. Photographic promiscuity is now one of our mores. It’s what we do: we shoot everything, not least ourselves.

In the revised version of the essay, Sontag says that “taking photographs has set up a chronic voyeuristic relation to the world.” Her claim is that photography has reframed the way we see the world and our place in it.

What we see is mediated by technology. When we look through the eye of the camera, everything is revealed as a possible photograph. This has an atomizing effect: people and experiences appear discrete, the sort of thing suitable for collection in the miscellany of memory.

One way of approaching Sontag’s deeper point here is through her discussion of this Leica advertisement:

![]()

The people in the advertisement evince fear and shock, but the man behind his viewfinder is self-possessed. The promise is that the camera will make you the master of all situations. The Soviets crushing the Prague Spring, the Woodstock festival, the war in Vietnam, the winter games in Sapporo, the Troubles in Northern Ireland – all of these are “equalized by the camera”. They are reduced to the status of the “Event”: something that is “worth seeing – and therefore worth photographing.”

An Accessible World

Sontag was critical of a reduction that takes place in the lives of the viewing public (itself an extraordinarily telling phrase). She wrote that photographs have the effect of “making us feel that the world is more available than it really is”.

We see photographs of people and events that are remote in space and time. This may seem to bring them closer, but the sense in which they are made available is a highly mitigated one. Elsewhere in On Photography, Sontag speaks of a “proximity which creates all the more distance”. She argues that “it is not reality that photographs make immediately accessible, but images”.

Flicking through a photo magazine, we encounter a disorienting welter of subjects: the horrific, the erotic, the mundane. Everything jostles for our attention as tokens of one all-engrossing category: “the interesting”. This confusion is the ordinary condition of today’s compulsive screen-stroker.

Sontag’s complaint about the “leveling” effect of media is nothing new. It goes back at least to the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard in the 1840s. At that time, new telegraph networks and faster printing presses meant that each morning more eyes were focused on news about elsewhere. Kierkegaard thought that as we become more curious about distant events, our lives lose intensity. We cease to see ourselves as concrete individuals and become members of that abstraction “the public”, whose solitary duty is to be informed, to be conversant with the topics of the day.

Like Kierkegaard, Sontag’s purpose was, broadly speaking, ethical. She was concerned with our sense of ourselves and our place in the world. She thought that photographs were displacing us. What is furthest in space and time now reaches us as quickly as what is closest. It is not that the far has drawn nearer, but that everything is held at an equal distance. Our sense of situatedness has been upset. We are simultaneously everywhere and nowhere – an all-seeing, incorporeal eye. Our sense of orientation, our sense of what is relevant to us, has diminished.

This may give a false impression of Sontag’s argument. Her political commitment is beyond question (just read about her 1968 visit to North Vietnam, or her 1993 staging of Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo). She was certainly not trying to justify inattention or insularity.

Sontag’s objection is primarily to the way we are transformed into, as she writes elsewhere, “customers or tourists of reality”. Our responsibility becomes perpetual consumption of what is served up by the media. We relate to the world beyond the media as if it were media, as if it were content.

Sontag’s criticism of “mediation” is, in part, about a loss of intensity. But more to the point, it is about (to use one of her key terms) a loss of complexity.

Reality?

Contact demands more than an image hitting the eye. It requires immersion, it requires physicality, it requires understanding. Sontag envisages a responsibility beyond that of the so-called “concerned spectator”, whose attention she describes elsewhere as “proximity without risk”.

In a late interview, Sontag said that she was for “complexity and the respect for reality.” But what exactly does she mean by reality? “Photography” begins:

We linger unregenerately in Plato’s cave, still reveling, our age-old habit, in mere image of the truth.

For Plato, reality is a world of abstract ideas hidden behind sensory experience. His cave-dwellers are prisoners forced to watch flickering, evanescent images cast on the wall. Knowledge alone can loosen our bonds, and allow us to discover the source of the illusion that we mistake for reality.

Sontag’s cave is a different proposition. It is the cave of the Cyclops and the Gorgon, where all that moves becomes ossified before that one enframing eye. What Sontag sought were not the truths of static facts, but those of lived experience. In the worn existentialist jargon, she was after authenticity in the relationship of the individual to themselves and to their society. She was also after presence, an immersion in the moment, so long as we do not assume this means the non-discursive presence advocated by her contemporaries in slogans such as “Be Here Now”.

Sontag was interested above all in enriching the sorts of stories that we tell ourselves and others. She was interested in “consciousness”, not in the narrow sense of the mind as opposed to body, but in the novelist’s sense of the narratives of embodied subjects. Understanding, for Sontag, is not a matter of taking things at face value, but a matter of interpretation. “Only that which narrates can make us understand,” she writes.

Sontag has a strong sense of the interpenetration of mind and world. Her conception of consciousness is not Platonic but Proustian. How we look at things profoundly influences what we see. We are not extricable from what happens to us. Our present is pregnant with our past. The world is not a composite of objects out there, which can be put in our pockets. Our experiences are not objects in here, which can be filed away in the mind’s albums.

The psychological distance required to record an experience does not leave that experience unchanged. Not only that, but those recordings can come to dominate and displace our narratives, our memories.

Memories in Flux

In the last of the On Photography essays, Sontag writes that photographs are “not so much an instrument of memory as an invention of it or a replacement”.

![]()

Our memories are in flux, our narratives are forever being rewritten. The photograph becomes iconic: as a tangible document to which we can return, it eclipses the subtle and always equivocal texture of multisensory association. That is what Aunt Léonie looked like. This is what happened on that trip to Combray.

Kodak knew this, too: humans forget, they said, but “snapshots remember”. To have a Kodak with you is to be able to capture the moment, to possess it. “They All Remembered the Kodak” – but perhaps it is all they remembered.

Our history thus begins to present itself as a set of snapshots, static events. Our memories are made readily available to us by the camera as things. But for Sontag, our memories are not possessions. Our memories possess us, haunt us.

Of course, photographs can haunt us too. In her last book, Sontag argued that we should let certain images do so. But her sense of the danger of what we might call a photographic relationship to reality is not only relevant today; it is liable to seem positively prescient.

The two decades since Sontag’s death in 2004 have seen the greatest changes in popular photographic practice since the Brownie brought photography to the masses a century earlier.

In 1973, Sontag spoke of the “omnipresence of cameras”. How does one trump a claim to ubiquity? When Sontag wrote that, only the most earnest shutterbug took their camera with them everywhere. But since her death cameras have become not only smaller but also indiscreet. The camera is no longer something one decides to pocket; it piggybacks on the presence of the smartphone.

The coupling of camera and internet has changed the nature of photography. Kodak tells us in a 2010 campaign that “the real Kodak moment happens when you share”. This marks an important shift in emphasis away from the experience one tried to capture and towards the experience of publicity.

We no longer have to wait to show others what we have seen. But more importantly, those others have changed. Not only can we show photos to more people, but the viewer no longer needs to be selected at all. Our audience has become vague: it is (that abstraction again) “the public”.

We now have a compulsion not only to record, but to share. And for what? Sontag said that everything exists to end in a photograph. Today everything exists to be scrolled past in a feed.

![]()

About the author: Andrew Milne is a Lecturer in Philosophy at The University of Western Australia. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. This article was originally published at The Conversation and is being republished under a Creative Commons license.